Awesome

Update

This version of React Chat was built using our Legacy React App Template based on React 0.12, ES5 and the now deprecated JSXTransformer. This legacy template is still available in our archived ServiceStackVS.Archive.vsix VS.NET Extension.

A newer version of React Chat based on our recommended and more modern React App VS.NET Template using TypeScript, React v15, JSPM and Redux is available at: https://github.com/ServiceStackApps/ReactChat

React Chat

is a port of ServiceStack Chat Server Events demo to React built with ServiceStackVS's new node.js-based ReactJS App VS.NET Template enabling an optimal iterative dev experience for creating optimized React.js Apps. This guide also includes an intro to Facebook's React library and Flux pattern and walks through how to use them to put together a React-based App.

Live Demo: http://react-chat.servicestack.net

Modern React.js Apps with .NET

The new ServiceStackVS ReactJS App template shares the same approach for developing modern Single Page Apps in VS.NET as the AngularJS App template by leveraging the node.js ecosystem for managing all aspects of Client App development using the best-in-class libraries:

- npm to manage node.js dependencies (bower, grunt, gulp)

- Bower for managing client dependencies (angular, jquery, bootstrap, etc)

- Grunt as the primary task runner for server, client packaging and deployments

- Gulp used by Grunt to do the heavy-lifting bundling and minification

The templates conveniently pre-configures the above libraries into a working out-of-the-box solution, including high-level grunt tasks to take care of the full-dev-cycle of building, packaging and deploying your app:

- 01-run-tests - Runs Karma JavaScript Unit Tests

- 02-package-server - Uses msbuild to build the application and copies server artefacts to

/wwwroot - 03-package-client - Optimizes and packages the client artefacts for deployment in

/wwwroot - 04-deploy-app - Uses MS WebDeploy and

/wwwroot_buld/publish/config.jsonto deploy app to specified server

Optimal Development and Deployment workflow

Fast dev iterations are one of the immediate benefits when developing JavaScript-based Apps, made possible since you're editing the same plain text files browsers execute, so they get quickly rendered after each refresh without needing to wait for the rebuilding of VS.NET projects or ASP.NET's AppDomain to restart.

This fast dev cycle also extends to ServiceStack Razor dynamic server pages which supports live-reloading of modified

.cshtmlRazor Views so they're view-able on-the-fly without an AppDomain restart.

For minimal friction, the Gulp/Grunt build system takes a non-invasive approach that works around normal web dev practices of being able to reference external css, js files - retaining the development experience of a normal static html website where any changes to html, js or css files are instantly visible after a refresh.

Then to package your app for optimal deployment to production, Gulp's useref plugin lets you annotate existing references with how you want them bundled. This is ideal as the existing external references (and their ordering) remains the master source for your Apps dependencies, reducing the maintenance and friction required in developing and packaging optimized Single Page Apps.

We can look at React Chat's dependencies to see how this looks:

<!--build:css css/app.min.css-->

<link rel="stylesheet" href="css/app.css" />

<!-- endbuild -->

<!-- build:js lib/js/jquery.min.js -->

<script src="bower_components/jquery/dist/jquery.js"></script>

<!-- endbuild -->

<!-- build:js lib/js/react.min.js -->

<script src="bower_components/react/react.js"></script>

<!-- endbuild -->

<!-- build:js lib/js/reflux.min.js -->

<script src="bower_components/reflux/dist/reflux.js"></script>

<!-- endbuild -->

<!-- build:remove -->

<script src="bower_components/react/JSXTransformer.js"></script>

<!-- endbuild -->

<script src="js/ss-utils.js"></script>

...

<!-- build:js js/app.jsx.js -->

<script type="text/jsx" src="js/components/Actions.js"></script>

<script type="text/jsx" src="js/components/User.jsx"></script>

<script type="text/jsx" src="js/components/Header.jsx"></script>

<script type="text/jsx" src="js/components/Sidebar.jsx"></script>

<script type="text/jsx" src="js/components/ChatLog.jsx"></script>

<script type="text/jsx" src="js/components/Footer.jsx"></script>

<script type="text/jsx" src="js/components/ChatApp.jsx"></script>

<!-- endbuild -->

During development the HTML comments are ignored and React Chat runs like a normal static html website. Then when packaging the client app for deployment (i.e. by running the 03-package-client task), the build annotations instructs Gulp on how to package and optimize the app ready for production.

As seen in the above example, each build instruction can span one or multiple references of the same type and optionally specify the target filename to write the compressed and minified output to.

Design-time only resources

Gulp also supports design-time vs run-time dependencies with the build:remove task which can be used to remove any unnecessary dependencies not required in production like react's JSXTransformer.js:

<!-- build:remove -->

<script src="bower_components/react/JSXTransformer.js"></script>

<!-- endbuild -->

React's JSXTransformer.js is what enables the optimal experience of letting you directly reference .jsx files in HTML as if they were normal .js files by transpiling and executing .jsx files directly in the browser at runtime - avoiding the need for any manual pre-compilation steps and retaining the fast F5 reload cycle that we've come to expect from editing .js files.

<!-- build:js js/app.jsx.js -->

<script type="text/jsx" src="js/components/Actions.js"></script>

<script type="text/jsx" src="js/components/User.jsx"></script>

<script type="text/jsx" src="js/components/Header.jsx"></script>

<script type="text/jsx" src="js/components/Sidebar.jsx"></script>

<script type="text/jsx" src="js/components/ChatLog.jsx"></script>

<script type="text/jsx" src="js/components/Footer.jsx"></script>

<script type="text/jsx" src="js/components/ChatApp.jsx"></script>

<!-- endbuild -->

Then when the client app is packaged, all .jsx files are compiled and minified into a single /js/app.jsx.js with the reference to JSXTransformer.js also stripped from the optimized HTML page as there's no longer any need to transpile and execute .jsx files at runtime.

Introducing React.js

React is a new library from Facebook that enables a new approach to rendering dynamic UI's, maintaining state and modularizing large complex JavaScript Apps.

Rather than attempting to be a full-fledged MVC framework, React is limited in scope around the V in MVC where it can even be used together as a high-performance view renderer with JavaScript's larger MVC frameworks.

Just Components

React benefits from its limited focus by having a simple but very capable API with a small surface area requiring very few concepts to learn - essentially centered around everything being a Component.

Conceptually speaking React Components are similar to Custom Elements in Web Components where they encapsulate presentation, state and behavior and are easily composable using a declarative XML-like syntax (JSX), or if preferred can be constructed in plain JavaScript.

Simple One-Way Data Binding

In contrast to AngularJS which popularized 2-way data-binding for the web, React offers a controlled one-way data flow that encourages composing your app into modular components that are declaratively designed to reflect how they should look at any point in time.

Whilst on the surface this may not appear as useful as a traditional 2-way data-binding system, React Apps are naturally easier to reason-about as instead of having to think about the serial effects of changes to your running App, your focus is instead on how your App should look like for a particular given state and React takes care of the hard work of calculating and batching all the imperative DOM mutations required to transition your App into its new State.

Virtual DOM

In order to change the UI, you just update a Components State and React will conceptually re-render the entire app so that it reflects the new state. Whilst this may sound inefficient, React's clever use of a Virtual DOM to capture a snapshot of your UI and its diff algorithm ensures that only the DOM elements that needs updating are changed - resulting in a responsive and high-performance UI.

Simple, Declarative, Modular Components

Components are at the core of React, they're the primary way to encapsulate a modular unit of functionality and can be composed together as we're used to doing with HTML.

A Component is simply a React class that implements a render method returning how it should look. As they're just lightweight JS classes they're suitable for encapsulating any level of granularity from a single HTML element:

var HelloMessage = React.createClass({

render: function() {

return <div>Hello {this.props.name}</div>;

}

});

to React Chat's entire application, which is itself comprised of more Components:

var ChatApp = React.createClass({

//...

render: function() {

return (

<div>

<Header channel={this.props.channel}

isAuthenticated={this.props.isAuthenticated}

activeSub={this.state.activeSub} />

<div ref="announce" id="announce">{this.state.announce}</div>

<div ref="tv" id="tv">{this.state.tvUrl}</div>

<Sidebar users={this.state.users} />

<ChatLog ref="chatLog"

messages={this.state.messages}

users={this.state.users}

activeSub={this.state.activeSub} />

<Footer channel={this.props.channel}

users={this.state.users}

activeSub={this.state.activeSub} />

</div>

);

}

});

To reference a component, the instance of the React class just needs to be in scope. Once available, components can be rendered into the specified DOM element with React.render(), e.g:

React.render(<HelloMessage name="John" />, document.body);

JSX

Whilst the components above look like they're composing and rendering HTML fragments, they're instead building up a JavaScript node graph representing the Virtual DOM what it should look like.

The mapping is a simple transformation enabled with Facebook's JSX JavaScript syntax extension letting you use an XML-like syntax to define JS object graphs, where our earlier <HelloMessage/> React component:

var HelloMessage = React.createClass({

render: function() {

return <div>Hello {this.props.name}</div>;

}

});

Gets transpiled to:

var HelloMessage = React.createClass({displayName: 'HelloMessage',

render: function() {

return React.createElement("div", null, "Hello ", this.props.name);

}

});

React relies on the built-in convention for using lowercase names to reference HTML elements and PascalCase names to reference React Components.

From this we can see that JSX just compiles to a nested graph of JS function calls. Knowing this we can see how to write components in plain JavaScript directly, without JSX. Whilst this is always possible, JSX is still preferred because of its familiar HTML-like syntax whose attributes and elements provide a more concise and readable form than the equivalent nested JavaScript function calls and object literals.

Virtual DOM vs HTML

Its close appearance to HTML may mistakenly give the impression that it also behaves like HTML, but as its instead a representation of JavaScript, it does have some subtle differences that you need to be aware of.

The modified HelloMessage component below illustrates some of these key differences:

var HelloMessage = React.createClass({

handleClick: function(event) {

//...

},

render: function() {

return (

<div className="hello" style={{marginLeft:10}} onClick={this.handleClick}>

Hello {this.props.name}

</div>

);

});

Firstly JavaScript keywords such as class and for shouldn't be used. Instead, React expects JavaScript DOM property names like className and htmlFor, respectively.

Next style accepts a JavaScript object literal for which styles to set, and requires identifiers to be in JS camelCase like marginLeft instead of CSS's margin-left.

There are a few exceptions, but in most cases integer values get converted into px e.g:

{marginLeft:10} => margin-left:10px

The {} braces denotes a JavaScript expression, so when double-braces are used like:

{ {marginLeft:10} }

It just denotes a JavaScript expression that returns the {marginLeft:10} object literal.

Unlike HTML which has string attributes, Component attributes can be assigned any JavaScript object which is how onClick can be assigned a direct reference to the this.handleClick method.

Synthetic Events

The other difference of onClick is that it uses a Synthetic Event system which mimics (and wraps) a native browser event, but uses a virtual implementation that behaves consistently across all browsers.

Like other attributes, event attributes are exposed using a JS camelCase convention prefixed with on so instead of click you'd use onClick. By default event handlers are triggered in the normal bubbling phase and can be instead be registered to trigger in the capture phase by appending Capture to the event name, e.g: onClickCapture.

Porting a JavaScript App to React

The exercise of porting Chat to a React-based app highlights some of the notable differences and benefits of a React-based App over a vanilla JavaScript or jQuery based App.

Modularity vs Lines of Code

As web apps go, Chat does a great job of implementing the core features of a chat application in just 170 lines of JavaScript, it's able to achieve this by leveraging a number of features in ss-utils.js like Declarative Events eliminating the boilerplate and book-keeping typically involved with firing and handling DOM events.

Sometimes rewriting your app to use a framework will result in a net savings in lines of code, typically due to replacing redundant code and bespoke implementations with built-in framework features, but in this case as there was no such boilerplate or repetitive code, so the lines of HTML and JS in the React port ended up doubling.

The increase in code is effectively the price paid for modularity. The original Chat is essentially a monolithic App developed in a single intertwined block of HTML + JS which is also the smallest unit of encapsulated functionality. The results in any change having the potential to impact any other part of the App so the entire context of the App needs to be kept into consideration with every change.

There's also very limited potential for re-use, with practically no opportunity to extract any code fragments in isolation and re-use as-is elsewhere. Whilst a monolithic App design is manageable (and requires less effort) in smaller code bases, it doesn't scale well in a larger and constantly evolving code-base.

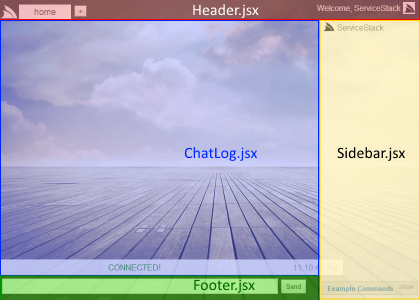

React Components

The first step into creating a React app is deciding how to structure the app, as React Components are just lightweight classes the number of components shouldn't affect the granularity in partitioning your app so you can happily opt for the most logical separation that suits your App.

For Chat, this was easy as it was already visually separated by different regions, allowing it to be naturally partitioned into the following distinct logical components:

As well as a top-level ChatApp, used to compose the different components together:

High-level Structure and Design First

The first step in porting to React is getting the layout and structure of your App right, so for the first pass just the HTML markup was extracted into each Component, where the initial cut of Footer.jsx before adding any behavior just looked like:

var Footer = React.createClass({

render: function() {

return (

<div id="bottom">

<input ref="txtMsg" id="txtMsg" type="text" />

<button id="btnSend" style={{marginLeft: 5}}>Send</button>

</div>

);

}

});

React has nice support of this gradual design-first dev workflow where the visual appearance of your App remains viewable after each stage of extracting the just HTML markup into its separate Components.

State and Communications between Components

The important concept to keep in mind when reasoning about React's design is that components are a projection for a given State. To enforce this, data flows unidirectionally down from the top-most Component (Owner) to its children via properties. In addition, Components can also maintain its own State which together with properties, are all that's used to dynamically render its UI on every state change.

We can visualize how data flows throughout a React App by tracking the flow of users through to the different React Chat components.

The list of active users for the entire App is sourced from the users collection in the top-level ChatApp component's State. It's then passed down to its child Sidebar and ChatLog components via properties:

var ChatApp = React.createClass({

//...

render: function() {

return (

<div>

...

<Sidebar users={this.state.users} />

<ChatLog ref="chatLog"

messages={this.state.messages}

users={this.state.users}

activeSub={this.state.activeSub} />

...

</div>

);

}

});

Accessing State and Properties

Each component has access to all properties assigned to it via its this.props collection. The Sidebar then uses this.props.users to generate a dynamic list of child User components for each currently subscribed user.

In addition to properties, Sidebar maintains its own hideExamples state (invisible to other components) which it uses to determine whether to show the Example Commands or not, as well as what appropriate show or hide action label to display.

Modify State with Callbacks

The Sidebar example below also shows how children are able to modify its parent state via the onClick={this.toggleExamples} callback, invoking the Sidebar's toggleExamples method and modifying the hideExamples state with this.setState() - which is the API used to modify a Components State and re-render its UI:

var Sidebar = React.createClass({

getInitialState: function() {

return { hideExamples: false };

},

toggleExamples: function(e) {

this.setState({ hideExamples: !this.state.hideExamples });

},

render: function() {

var height = this.state.hideExamples ? '25px' : 'auto',

label = this.state.hideExamples ? 'show' : 'hide';

return (

<div id="right">

<div id="users">

{this.props.users.map(function(user) {

return <User key={user.userId} user={user} />;

})}

</div>

<div id="examples" style={{ height: height }}>

<span onClick={this.toggleExamples}>{label}</span>

...

</div>

</div>

);

}

});

Finally user data makes its way down to the child User Component, but this time only gets passed a single user object which it uses to render the users avatar and name:

var User = React.createClass({

handleClick: function() {

Actions.userSelected(this.props.user);

},

render: function() {

return (

<div className="user">

<img src={this.props.user.profileUrl || "/img/no-profile64.png"}/>

<span onClick={this.handleClick}>

{this.props.user.displayName}

</span>

</div>

);

}

});

Decoupled and Reusable Components

What's telling about Components is that they don't have a dependency on its parent Component as it's able to render everything it needs by just looking at its assigned properties and localized state. This decoupling is what allows Components to be re-usable and much easier to reason-about as its behavior can be determined in isolation, unaffected by any other external State or Component.

React's strict one-way data flow does present a challenge with how a child component can communicate with the rest of the application and vice versa. To tackle this Facebook has released a guidance architecture called flux which introduces the concept of a central Dispatcher, Actions and Stores.

Listening to Actions

In the User component we start to see a glimpse of this with the Actions.userSelected that's triggered whenever a users name is clicked. Effectively this is just raising an event visible to the rest of the application which any component can listen to and handle.

In this case the Footer component is interested whenever a user is clicked so it can pre-populate the Chat TextBox with the users name, ready to send a private message. For this we use Reflux's convenience listenTo mixin to listen to a specific action:

var Footer = React.createClass({

mixins:[

Reflux.listenTo(Actions.userSelected,"userSelected"),

Reflux.listenTo(Actions.setText,"setText")

],

userSelected: function(user) {

this.setText("@" + user.displayName + " ");

}

setText: function(txt) { ... },

...

});

This can be made even shorter with the Reflux.listenToMany convenience mixin which lets you listen to ALL actions for which a Component provides implementations for, e.g:

var Footer = React.createClass({

mixins:[ Reflux.listenToMany(Actions) ],

userSelected: function(user) {

this.setText("@" + user.displayName + " ");

}

setText: function(txt) { ... },

...

});

Whilst this does save boilerplate, it's less explicit than declaring which specific actions your Component listens to, with the potential for accidental naming clashes in larger apps.

Flux vs Reflux

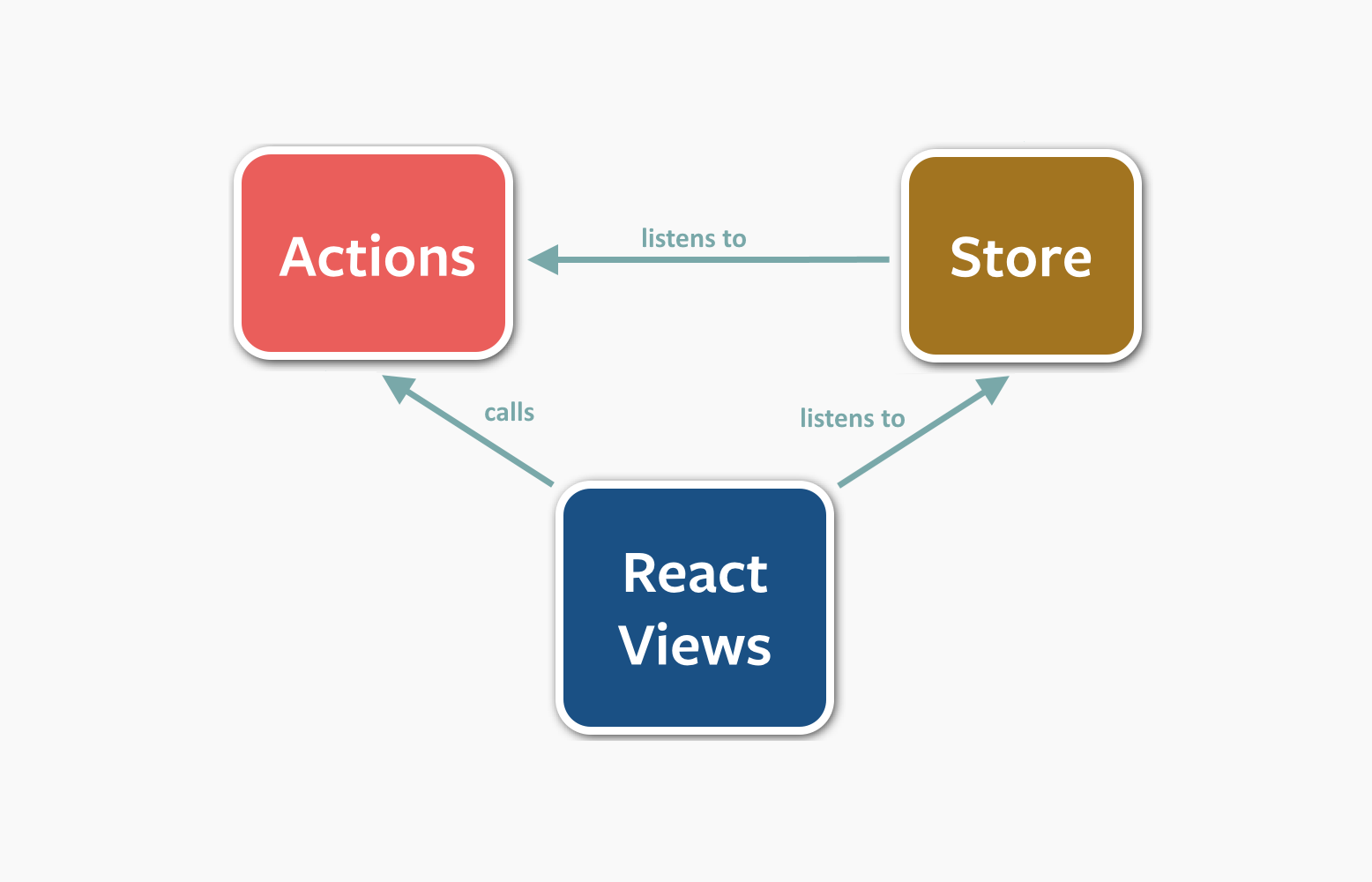

Earlier we introduced Flux - Facebook's guidance for designing large React apps by adopting a unidirectional data flow architecture in favor of a traditional MVC pattern. Whilst Flux is primarily meant to serve as an architectural pattern, Facebook also provide implementations for Flux concepts in the Flux repo and reference TodoMVC application.

They also provide the diagram below to help illustrate the structure and data flow of a Flux application and how its different concepts fit together:

.

.

In contrast to React's small and beautifully simple, purpose-specific API, Flux introduces a lot of concepts, boilerplate, moving pieces and indirection for relatively little value. Whilst the primary Actions and Stores concepts in Flux are sound, the implementation in Flux TodoMVC wont be winning any awards for simplicity, code-size, clarity or readability.

Luckily Flux is an optional external library and React has a thriving community who are able to step in with more elegant solutions, one of the standouts in this area is Reflux, a simpler re-imagination of the Flux architecture that's streamlined down to just:

.

.

Simply, Components listen to Store events to get notified when their state has changed and can invoke Actions which Stores (and anything else) can listen and react to.

Reflux also includes a number of convenience API's to reduce the boilerplate required when hooking the different pieces together. More information about the inspiration, benefits and differences of Reflux vs Flux can be found in the informative posts below:

Creating Actions

Creating actions is an example of one the areas that's much improved with Reflux which is able to create multiple actions in a single function call, which made it trivial to define all Actions used throughout React Chat with just:

var Actions = Reflux.createActions([

"didConnect",

"addMessages",

"removeAllMessages",

"recordMessage",

"refreshUsers",

"showError",

"logError",

"announce",

"userSelected",

"setText"

]);

Depending on number of actions in your App, you may prefer to logically group actions in multiple variables.

Once defined, actions can be triggered like a normal function call, e.g:

Actions.userSelected(user);

Which as a result can be invoked from anywhere (i.e. not just limited to Components). E.g. React Chat invokes them in Server Event Callbacks to trigger Store updates:

$(this.source).handleServerEvents({

handlers: {

onJoin: Actions.refreshUsers,

onLeave: Actions.refreshUsers,

chat: function (msg, e) {

Actions.addMessages([msg]);

}

},

...

});

This is the essence of how ChatApp works, with any Chat messages sent in Footer.jsx posted using ajax to the back-end ServerEvents Services which in turn fires local JavaScript ServerEvent handlers that invokes the global refreshUsers and addMessages Actions in order to update the App's local messages and users State.

Stores

Stores are a Flux concept used to maintain application state, I like to think of them as Data Controllers that own and are responsible for keeping models updated, who also notify listeners whenever they're changed.

Typically you would setup a different Store to manage different model and collection types, e.g. React Chat has a MessagesStore which holds all the messages that should appear in the ChatLog as well as a UsersStore to maintain the list of currently subscribed users which gets updated when anyone calls the Actions.refreshUsers Action. Once UsersStore gets back an updated list of users it then notifies all its listeners with the updated users collection with the this.trigger() API:

var UsersStore = Reflux.createStore({

init: function () {

this.listenTo(Actions.refreshUsers, this.refreshUsers);

this.users = [];

},

refreshUsers: function () {

var $this = this;

$.getJSON(AppData.channelSubscribersUrl, function (users) {

var usersMap = {};

$.map(users, function (user) {

usersMap[user.userId] = user;

});

$this.users = $.map(usersMap, function (user) { return user; });

$this.trigger($this.users);

});

}

});

As UsersStore only needs to listen to a single action I'll prefer to use the explicit this.listenTo(action, callback) API. Although for Stores like MessagesStore that needs to listen to multiple actions, you can make use of the convenient this.listenToMany(actions) API to reduce the boilerplate for registering multiple individual listeners, e.g:

var MessagesStore = Reflux.createStore({

init: function () {

this.listenToMany(Actions);

this.messages = [];

},

logError: function () { ... },

addMessages: function (msgs) { ... },

removeAllMessages: function () { ... },

...

});

Listening to Stores

Listening to Store events is similar to listening to Actions which can be registered using the Reflux.listenTo() convenience mixin, defining which method to call whenever a Store is updated.

ChatApp uses this to listen for updates from the MessagesStore and UsersStore, it's also the only Component that listens directly to Store events which it uses to updates its local state. The updated messages and users then flow down to child components via normal properties:

var ChatApp = React.createClass({

mixins:[

Reflux.listenTo(MessagesStore,"onMessagesUpdate"),

Reflux.listenTo(UsersStore,"onUsersUpdate")

],

onMessagesUpdate: function(messages) {

this.setState({ messages: messages });

},

onUsersUpdate: function(users) {

this.setState({ users: users });

},

render: function() {

var showTv = this.state.tvUrl ? 'block' : 'none';

return (

<div>

...

<ChatLog messages={this.state.messages}

users={this.state.users} />

...

<Footer users={this.state.users} />

</div>

);

}

...

});

The Flux Application Architecture refers to these top-level Components which connect to Stores and passes its data down to its descendants as Controller Views which is a recommended practice in order to be able to reduce dependencies and keep Child Components as functionally pure as possible.

ReactJS App Deployments

Once your app is in a state that's ready for deployment we can make use of the grunt tasks to package and optimize the App and deploy it via Web Deploy.

The /wwwroot_build folder contains the necessary files required for deployments including:

/wwwroot_build

/deploy # copies all files in folder to /wwwroot

appsettings.txt # production appsettings to override dev defaults

/publish

config.json # deployment config for WebDeploy deployments

02-package-server.bat # copies over server assets to /wwwroot

03-package-client.bat # optimizes client assets and copies to /wwwroot

04-deploy-app.bat # deploys /wwwroot using remote settings in config.json

package-and-deploy.bat # runs build tasks 02 - 04 in 1 step

The minimum steps to deploy an app is to fill in config.json with the remote IIS WebSite settings as well as a UserName and Password of a User that has permission to remote deploy an app:

{

"iisApp": "AppName",

"serverAddress": "deploy-server.example.com",

"userName": "{WebDeployUserName}",

"password" : "{WebDeployPassword}"

}

Then just run the package-and-deploy grunt task (or .bat script) which copies over the the server and client assets into the /wwwroot folder which contain the physical files of what gets deployed.

The package-server task will copy over the required .NET .dll and ASP.NET files as well as any files in /wwwroot_build/deploy which can be used to customize the production website.

The package-client task also optimizes any .jsx, .js and .css so only the bundled and minified versions get deployed. The resulting website that ends up getting deployed looks something like:

/wwwroot

/css

/img

/js

app.jsx.js

/lib

jquery.min.js

react.min.js

reflux.min.js

appsettings.txt

default.cshtml

Global.asax

web.config

This folder is then packaged into a webdeploy.zip file and deployed to the remote server, after it's finished running you will be able to run your app on the remote server which for React Chat is: http://react-chat.servicestack.net/

This is just a brief overview of packaging and deploying with the VS.NET templates Grunt/Gulp build systems, more in-depth documentation can be found in: