Awesome

Browser Rendering Optimization

Notes on browser rendering optimization and hitting 60fps smoothness!

Before understanding how to optimise web sites and applications for efficient rendering, it’s important to understand what is actually going on in the browser between the code you write and the pixels being drawn to screen.

There are six different tasks a browser performs to accomplish all this:

- Downloading and parsing HTML, CSS and JavaScript

- Evaluating JavaScript

- Calculating styles for elements

- Laying out elements on the page

- Painting the actual pixels of elements

Sometimes you may hear the term "rasterize" used in conjunction with paint. This is because painting is actually two tasks: 1) creating a list of draw calls, and 2) filling in the pixels. The latter is called "rasterization" and so whenever you see paint records in DevTools, you should think of it as including rasterization.

Putting the user in the center of performance

- 100 milliseconds

- Respond to a user action within this time window and they will feel like the result is immediate. Any longer and that connection between action and reaction breaks.

- 1 second

- Within this window, things feel part of a natural and continuous progression of tasks. Beyond it, the user will lose focus on the task they were performing. For most users on the web, loading a page or changing views represents a task.

- 16 milliseconds

- Given a screen that is updating 60 times per second, this window represents the time to get a single frame to the screen (Professor Math says 1000 ÷ 60 = ~16). People are exceptionally good at tracking motion, and they dislike it when their expectation of motion isn’t met, either through variable frame rates or periodic halting.

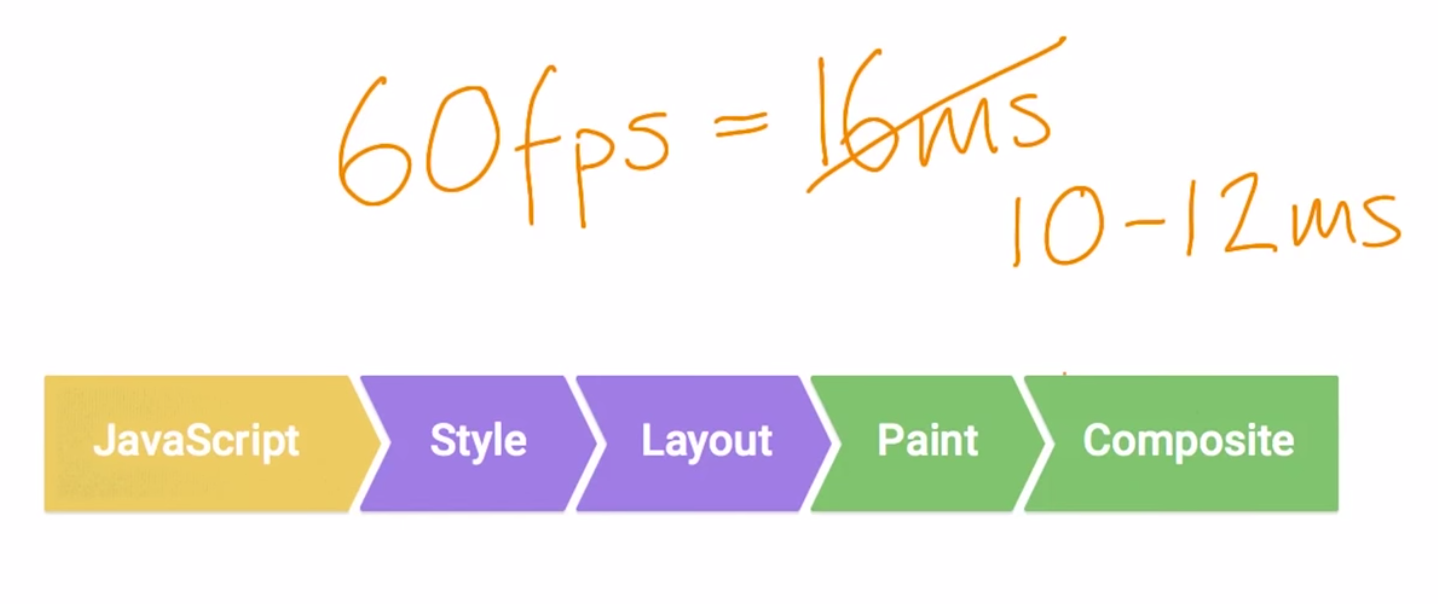

60fps = 16ms/frame, but you actually get only around 10-12ms to do all your work due to browser overhead.

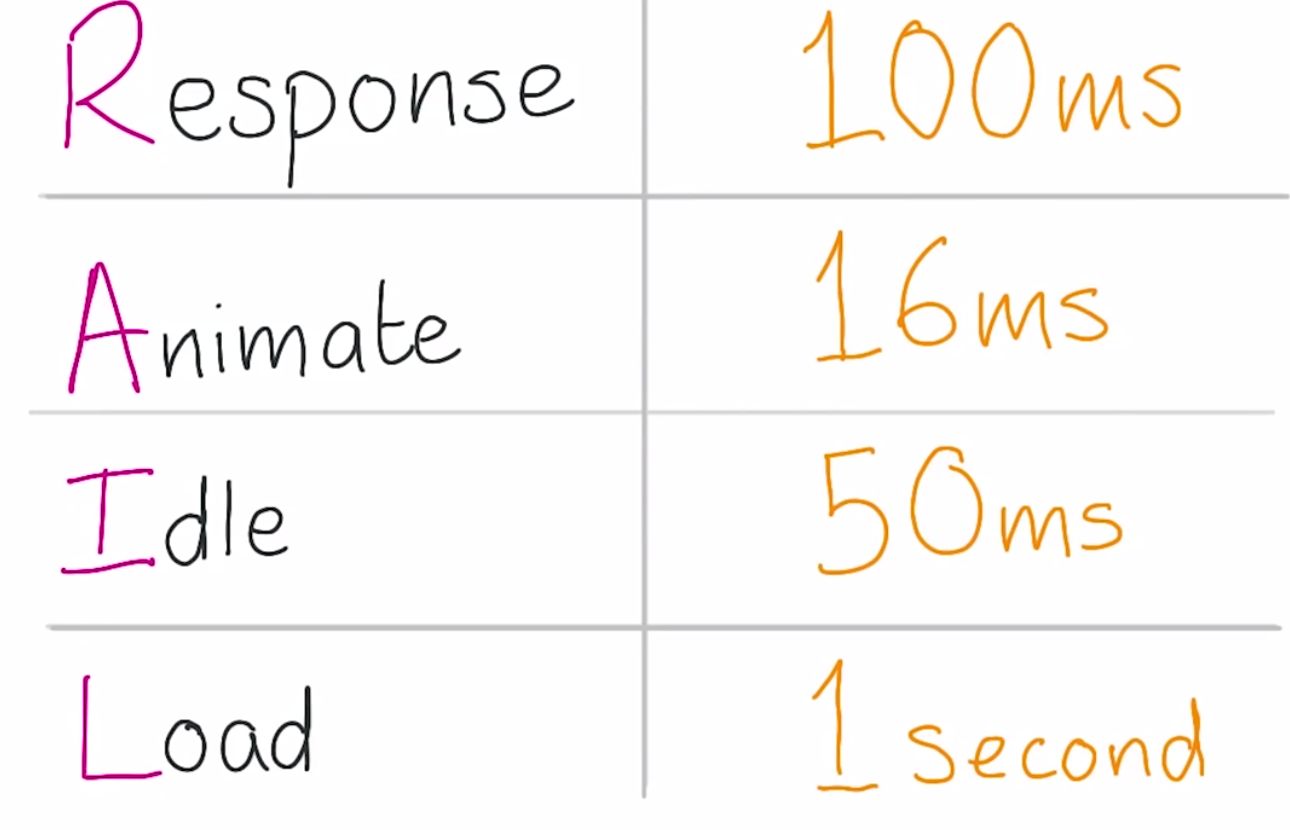

App Life Cycles (RAIL)

- Response

- Animations

- Idle

- Load (XHR, Websockets, HTML imports etc.)

Actual Chronological Order

- Load (~1 sec) Initial page load. Download and render your critical resources here.

- Idle (~ 50ms chunks) Do all non-essential work to ensure interactions that occur later on feel instantaneous. eg. lazy load items, do pre-animation calcs etc.

- Response (~100ms) On interaction, respond within 100ms.

- Animations (~16ms) In reality we get ~12ms since the browser has some overhead.

What happens during style changes?

For example, during an opacity change or transform animation, only the composite is triggered.

- The page isn't receiving any new HTML, so the DOM doesn't need to be built.

- The page isn't receiving any new CSS, so the CSSOM doesn't need to be built.

- The page isn't receiving any new HTML or CSS, so the Render Tree doesn't need to be touched.

- If an opacity or transform changes affects element on its own layer, layout won't need to be run.

- If an opacity or transform changes affects element on its own layer, paint won't need to be run.

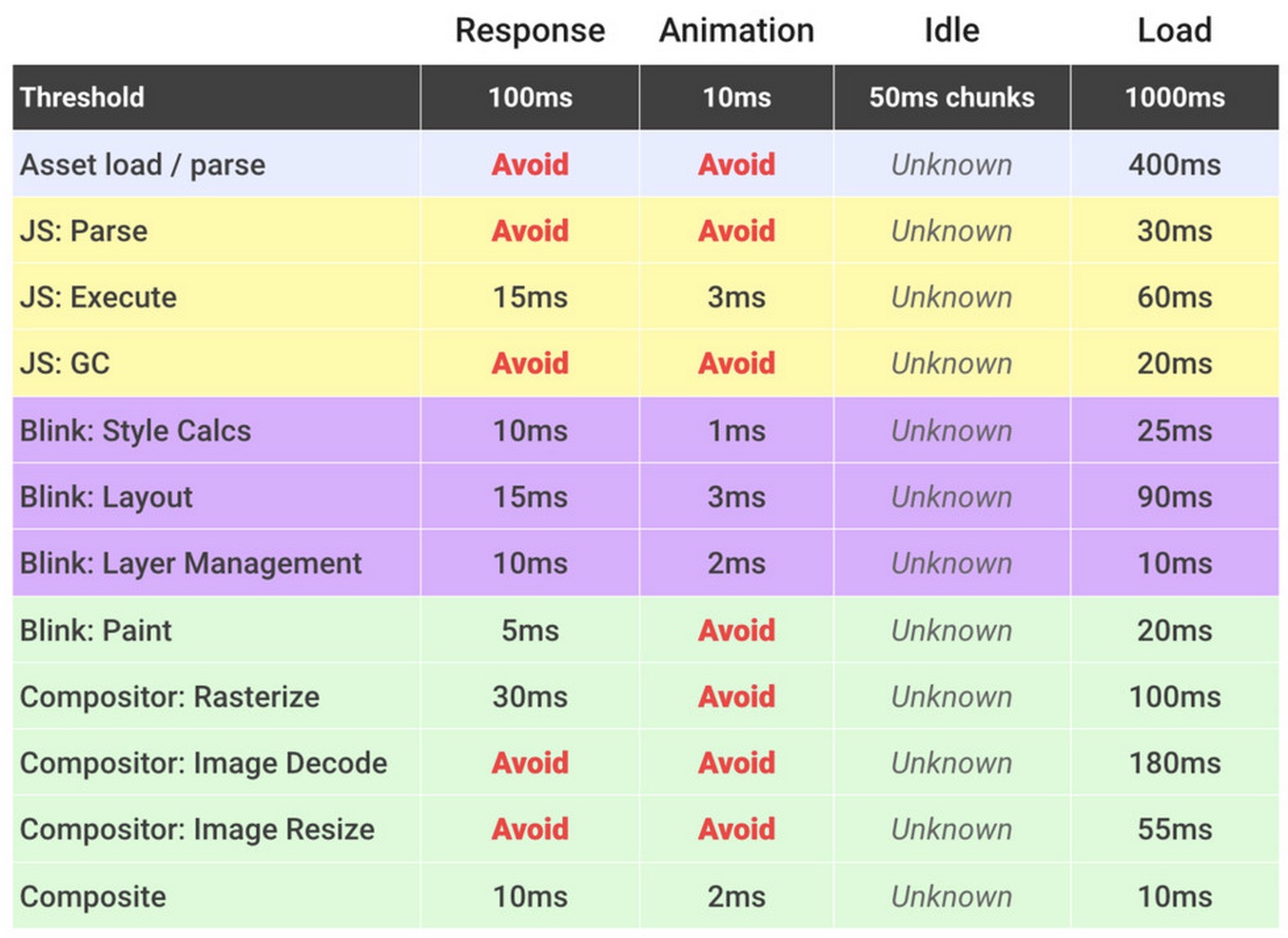

For JavaScript code to run faster

- Don't concentrate much on micro optimizations eg. for-loop vs while etc, since different JS engines (V8 etc.) handle it in different ways.

- JS can trigger every part of the rendering pipeline(Style, layout, paint and compositing changes), hence run it as early as possible in each frame.

Animation

- 'requestAnimationFrame' is the goto tool for creating animation.

- Schedules the JavaScript to run at the earliest possible moment in each frame.

- The browser can optimize concurrent animations together into a single reflow and repaint cycle, leading to higher fidelity animation. For example, JS-based animations synchronized with CSS transitions or SVG SMIL.

- Plus, if you’re running the animation loop in a tab that’s not visible, the browser won’t keep it running, which means less CPU, GPU, and memory usage, leading to much longer battery life.

- Browser has to render frames at 60fps ie. 16ms/frame.

- Due to browser overhead, we get around 10ms, so JS has about 3ms time.

- JavaScript -> Style -> Layout -> Painting -> Composite

- Do not use setTimout or setInterval for animations since JS engine does not pay attention to the rendering pipeline when executing this.

- For IE9 - use 'requestAnimationFrame' with Polyfill.

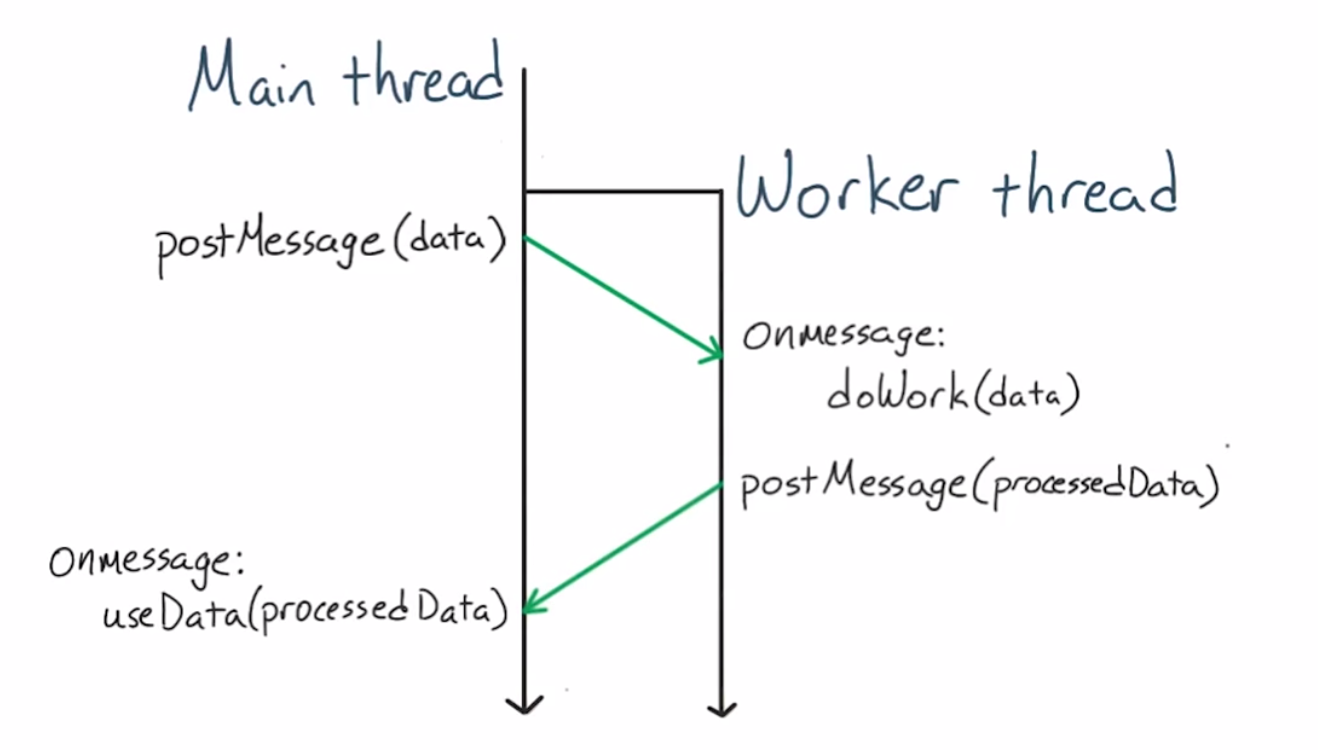

Webworkers

- Webworkers provide an interface for spawning scripts to run in the background - in a totally different scope than the main window and also in separate thread.

- Webworkers and the main thread can communicate with each other.

Styles and Layout (Recalc Styles)

- The cost of recalculate styles scales linearly with the number of elements on the page.

- BEM: Block Element Modifier: Use this style for CSS selectors.

- Class matching is often the fastest selector in modern browsers.

- Reducing 'Recalculate Styles' time.

- Reduce affected elements (fewer changes to render tree)

- Reduce selector complexity (fewer tags & class names to select elements)

- 'Forced synchronous layout' occurs when you ask the browser to run 'layout' first inside the JavaScript section and then do 'style' calcs and then layout is run again. Try to avoid it. Chrome dev tools (flame chart) helps to identify this.

- Read layout properties and batch your style changes to avoid running layout as much as possible.

- Layout thrashing happens when you do a 'forced synchronous layout' many times in succession.

Repaints and Reflows

Painting is the process by which the browser takes its abstract collection of elements with all their properties, and actually calculates the pixels to draw. This includes calculating styles such as box shadows and gradients, as well as resizing images. A repaint occurs when changes are made to an elements skin that changes visibility, but do not affect its layout. Examples of this include outline, visibility, or background color. According to Opera, repaint is expensive because the browser must verify the visibility of all other nodes in the DOM tree.

A reflow is even more critical to performance because it involves changes that affect the layout of a portion of the page (or the whole page). Reflow of an element causes the subsequent reflow of all child and ancestor elements as well as any elements following it in the DOM. According to Opera, most reflows essentially cause the page to be re-rendered.

So, if they’re so awful for performance, what causes a reflow?

Unfortunately, lots of things. Among them some which are particularly relevant when writing CSS:

- Resizing the window.

- Changing the font.

- Adding or removing a stylesheet.

- Content changes, such as a user typing text in an input box.

- Activation of CSS pseudo classes such as :hover (in IE the activation of the pseudo class of a sibling)

- Manipulating the class attribute.

- A script manipulating the DOM.

- Calculating offsetWidth and offsetHeight.

- Setting a property of the style attribute

For the complete list check Paul Irish's gist

Compositing and Painting

- Update Layer tree: Happens when Chrome's internal engine (Blink) figures out what layers are needed for the page. It looks at the styles of the elements and figures out what order everything should be in and how many layers it needs.

- You can add independent elements of the page to it's own layer. However, adding a lot fo layers comes with a cost - so use it wherever it makes sense.

- Adding layers using CSS:

- Conventional way - supported in all browsers:

transform: translatez(o); - New way - Chrome/Firefox support/No IE-Edge:

will-change: transform;

- Conventional way - supported in all browsers:

- Composite Layer: Is where the browser is putting the page together to center the screen.

Thanks to Paul Lewis and Cameron Pittman for their course on Udacity, which presented deeper insights to this topic.