Awesome

Benchee

If you have benchmarked using elixir 1.14.0 - 1.16.0-rc.0, please check out known issues

Library for easy and nice (micro) benchmarking in Elixir. Benchee allows you to compare the performance of different pieces of code at a glance. It is also versatile and extensible, relying only on functions. There are also a bunch of plugins to draw pretty graphs and more!

Benchee runs each of your functions for a given amount of time after an initial warmup, it then measures their run time and optionally memory consumption. It then shows different statistical values like average, standard deviation etc. See features.

Benchee has a nice and concise main interface, its behavior can be altered through lots of configuration options:

list = Enum.to_list(1..10_000)

map_fun = fn i -> [i, i * i] end

Benchee.run(

%{

"flat_map" => fn -> Enum.flat_map(list, map_fun) end,

"map.flatten" => fn -> list |> Enum.map(map_fun) |> List.flatten() end

},

time: 10,

memory_time: 2

)

Produces the following output on the console:

Operating System: Linux

CPU Information: AMD Ryzen 9 5900X 12-Core Processor

Number of Available Cores: 24

Available memory: 31.25 GB

Elixir 1.16.0-rc.1

Erlang 26.1.2

JIT enabled: true

Benchmark suite executing with the following configuration:

warmup: 2 s

time: 10 s

memory time: 2 s

reduction time: 0 ns

parallel: 1

inputs: none specified

Estimated total run time: 28 s

Benchmarking flat_map ...

Benchmarking map.flatten ...

Calculating statistics...

Formatting results...

Name ips average deviation median 99th %

flat_map 3.79 K 263.87 μs ±15.49% 259.47 μs 329.29 μs

map.flatten 1.96 K 509.19 μs ±51.36% 395.23 μs 1262.27 μs

Comparison:

flat_map 3.79 K

map.flatten 1.96 K - 1.93x slower +245.32 μs

Memory usage statistics:

Name Memory usage

flat_map 625 KB

map.flatten 781.25 KB - 1.25x memory usage +156.25 KB

**All measurements for memory usage were the same**

The aforementioned plugins like benchee_html make it possible to generate nice looking HTML reports, where individual graphs can also be exported as PNG images:

Table of Contents

- Table of Contents

- Features

- Installation

- Usage

- Known Issues

- Plugins

- Contributing

- Development

- Copyright and License

Features

- first runs the functions for a given warmup time without recording the results, to simulate a "warm"/running system

- measures memory usage

- provides you with lots of statistics

- plugin/extensible friendly architecture so you can use different formatters to display benchmarking results as HTML, markdown, JSON and more

- measure not only time, but also measure memory and reductions

- profile right after benchmarking

- as precise as it can get, measure with up to nanosecond precision (Operating System dependent)

- nicely formatted console output with units scaled to appropriately (nanoseconds to minutes)

- (optionally) measures the overhead of function calls so that the measured/reported times really are the execution time of your_code without that overhead.

- hooks to execute something before/after a benchmarking invocation, without it impacting the measured time

- execute benchmark jobs in parallel to gather more results in the same time, or simulate a system under load

- well documented & well tested

Statistics

Provides you with the following statistical data:

- average - average execution time/memory usage (the lower the better)

- ips - iterations per second, aka how often can the given function be executed within one second (the higher the better - good for graphing), only for run times

- deviation - standard deviation (how much do the results vary), given as a percentage of the average (raw absolute values also available)

- median - when all measured values are sorted, this is the middle value. More stable than the average and somewhat more likely to be a typical value you see, for the most typical value see mode. (the lower the better)

- 99th % - 99th percentile, 99% of all measured values are less than this - worst case performance-ish

In addition, you can optionally output an extended set of statistics:

- minimum - the smallest value measured for the job (fastest/least consumption)

- maximum - the biggest run time measured for the job (slowest/most consumption)

- sample size - the number of measurements taken

- mode - the measured values that occur the most. Often one value, but can be multiple values if they occur exactly as often. If no value occurs at least twice, this value will be

nil.

Installation

Add :benchee to your list of dependencies in mix.exs:

defp deps do

[

{:benchee, "~> 1.0", only: :dev}

]

end

Install via mix deps.get and then happy benchmarking as described in Usage :)

Elixir versions supported/tested against are 1.7+. It should theoretically still work with 1.4, 1.5 & 1.6 but we don't actively test/support it as installing them on current CI systems is not supported out of the box.

Usage

After installing just write a little Elixir benchmarking script:

list = Enum.to_list(1..10_000)

map_fun = fn i -> [i, i * i] end

Benchee.run(

%{

"flat_map" => fn -> Enum.flat_map(list, map_fun) end,

"map.flatten" => fn -> list |> Enum.map(map_fun) |> List.flatten() end

}

)

(names can also be specified as :atoms if you want to)

This produces the following output:

tobi@speedy:$ mix run samples/run_defaults.exs

Operating System: Linux

CPU Information: Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-4790 CPU @ 3.60GHz

Number of Available Cores: 8

Available memory: 15.61 GB

Elixir 1.8.1

Erlang 21.2.7

Benchmark suite executing with the following configuration:

warmup: 2 s

time: 5 s

memory time: 0 ns

parallel: 1

inputs: none specified

Estimated total run time: 14 s

Benchmarking flat_map...

Benchmarking map.flatten...

Name ips average deviation median 99th %

flat_map 2.34 K 427.78 μs ±16.02% 406.29 μs 743.01 μs

map.flatten 1.22 K 820.87 μs ±19.29% 772.61 μs 1286.35 μs

Comparison:

flat_map 2.34 K

map.flatten 1.22 K - 1.92x slower +393.09 μs

See Features for a description of the different statistical values and what they mean.

If you're looking to see how to make something specific work, please refer to the samples directory. Also, especially when wanting to extend Benchee, check out the hexdocs.

Configuration

Benchee takes a wealth of configuration options, however those are entirely optional. Benchee ships with sensible defaults for all of these.

In the most common Benchee.run/2 interface configuration options are passed as the second argument in the form of an keyword list:

Benchee.run(%{"some function" => fn -> magic end}, print: [benchmarking: false])

The available options are the following (also documented in hexdocs).

warmup- the time in seconds for which a benchmarking job should be run without measuring anything before "real" measurements start. This simulates a "warm"/running system. Defaults to 2.time- the time in seconds for how long each individual scenario (benchmarking job x input) should be run for measuring the execution times (run time performance). Defaults to 5.memory_time- the time in seconds for how long memory measurements should be conducted. Defaults to 0 (turned off).reduction_time- the time in seconds for how long reductions are measured should be conducted. Defaults to 0 (turned off).inputs- a map or list of two element tuples. If a map, the keys are descriptive input names and values are the actual input values. If a list of tuples, the first element in each tuple is the input name, and the second element in each tuple is the actual input value. Your benchmarking jobs will then be run with each of these inputs. For this to work your benchmarking function gets the current input passed in as an argument into the function. Defaults tonil, aka no input specified and functions are called without an argument. See Inputs.formatters- list of formatters either as a module implementing the formatter behaviour, a tuple of said module and options it should take or formatter functions. They are run when usingBenchee.run/2or you can invoke them throughBenchee.Formatter.output/1. Functions need to accept one argument (which is the benchmarking suite with all data) and then use that to produce output. Used for plugins & configuration. Also allows the configuration of the console formatter to print extended statistics. Defaults to the builtin console formatterBenchee.Formatters.Console. See Formatters.measure_function_call_overhead- Measure how long an empty function call takes and deduct this from each measured run time. This overhead should be negligible for all but the most micro benchmarks. Defaults to false.pre_check- whether or not to run each job with each input - including all given before or after scenario or each hooks - before the benchmarks are measured to ensure that your code executes without error. This can save time while developing your suites. Defaults tofalse.parallel- the function of each benchmarking job will be executed inparallelnumber processes. Ifparallel: 4then 4 processes will be spawned that all execute the same function for the given time. Whentimeseconds have passed, 4 new processes will be spawned for the next scenario (meaning a new input or another function to be benchmarked). This gives you more data in the same time, but also puts load on the system interfering with benchmark results. For more on the pros and cons of parallel benchmarking check the wiki. Defaults to 1 (no parallel execution).save- specify apathwhere to store the results of the current benchmarking suite, tagged with the specifiedtag. See Saving & Loading.load- load saved suite or suites to compare your current benchmarks against. Can be a string or a list of strings or patterns. See Saving & Loading.print- a map or keyword list from atoms totrueorfalseto configure if the output identified by the atom will be printed during the standard Benchee benchmarking process. All options are enabled by default (true). Options are::benchmarking- print when Benchee starts benchmarking a new job (Benchmarking name ...) as well as when statistics are being calculated or formatting begins.:configuration- a summary of configured benchmarking options including estimated total run time is printed before benchmarking starts:fast_warning- warnings are displayed if functions are executed too fast leading to inaccurate measures

:unit_scaling- the strategy for choosing a unit for durations, counts & memory measurements. May or may not be implemented by a given formatter (The console formatter implements it). When scaling a value, Benchee finds the "best fit" unit (the largest unit for which the result is at least 1). For example, 1_200_000 scales to1.2 M, while800_000scales to800 K. Theunit_scalingstrategy determines how Benchee chooses the best fit unit for an entire list of values, when the individual values in the list may have different best fit units. There are four strategies, defaulting to:best::best- the most frequent best fit unit will be used, a tie will result in the larger unit being selected.:largest- the largest best fit unit will be used:smallest- the smallest best fit unit will be used:none- no unit scaling will occur.

:before_scenario/after_scenario/before_each/after_each- read up on them in the hooks sectionprofile_after- accepts any of the following options:- a boolean -

truewill enable profiling with the default profiler (:eprof) andfalsewill disable profiling. Defaults tofalse. - a profiler - either as a tuple of

{profiler, opts}(e.g.,{:fprof, [sort: :own]}) or just the profiler (e.g.,:fprof), which is equivalent to{profiler, []}. The accepted built-in profilers are:cprof,:eprofand:fprof.

- a boolean -

Metrics to measure

Benchee can't only measure execution time, but also memory consumption and reductions!

You can measure one of these metrics, or all at the same time. The choice is up to you. Warmup will only occur once though, the time for measuring the metrics are governed by time, memory_time and reduction_time configuration values respectively.

By default only execution time is measured, memory and reductions need to be opted in by specifying a non 0 time amount.

Measuring time

This is the default, which you'll most likely want to use as you want to measure how fast your system processes something or responds to a request. Benchee does its best to measure time as accurately and as scoped to your function as possible.

Benchee.run(

%{

"something_great" => fn -> cool_stuff end

},

warmup: 1,

time: 5,

memory_time: 2,

reduction_time: 2

)

A note on time measurement accuracy

From system to system the resolution of the clock can vary.

Generally speaking we have seen accuracies down to 1 nanosecond on Linux and ~1 microsecond onb both OSX and Windows. We have also seen accuracy as low as 10ms on Windows in a CI environment. These numbers are not a limitation of Benchee, but of the Operating System (or at the very least how erlang makes it available).

If your benchmark takes 100s of microseconds this likely has no/little impact, but if you want to do extremely nano benchmarks we recommend doing them on Linux.

So, what happens if a function executes too fast for Benchee to measure? If Benchee recognizes this (not always possible) it will automatically take the function and repeat it multiple times. This way a function that takes 2 microseconds will take ~20 microseconds and differences can be measured even with microsecond accuracy. Naturally, this comes at several disadvantages:

- The looping/repetition code is now measured alongside the function

- essentially every single measurement is now an average across 10 runs making lots of statistics less meaningful

Benchee will print a big warning when this happens.

Measuring Memory Consumption

Starting with version 0.13, users can now get measurements of how much memory their benchmarked scenarios use. The measurement is limited to the process that Benchee executes your provided code in - i.e. other processes (like worker pools)/the whole BEAM isn't taken into account.

This measurement is not the actual effect on the size of the BEAM VM size, but the total amount of memory that was allocated during the execution of a given scenario. This includes all memory that was garbage collected during the execution of that scenario.

This measurement of memory does not affect the measurement of run times.

In cases where all measurements of memory consumption are identical, which happens very frequently, the full statistics will be omitted from the standard console formatter. If your function is deterministic, this should always be the case. Only in functions with some amount of randomness will there be variation in memory usage.

Memory measurement is disabled by default, you can choose to enable it by passing memory_time: your_seconds option to Benchee.run/2:

Benchee.run(

%{

"something_great" => fn -> cool_stuff end

},

memory_time: 2

)

Memory time can be specified separately as it will often be constant - so it might not need as much measuring time.

A full example, including an example of the console output, can be found here.

Measuring Reductions

Starting in versions 1.1.0 Benchee can measure reductions - but what are reductions?

In short, it's not very well defined but a "unit of work". The BEAM uses them to keep track of how long a process has run. As the Beam Book puts it as follows:

BEAM solves this by keeping track of how long a process has been running. This is done by counting reductions. The term originally comes from the mathematical term beta-reduction used in lambda calculus.

The definition of a reduction in BEAM is not very specific, but we can see it as a small piece of work, which shouldn’t take too long. Each function call is counted as a reduction. BEAM does a test upon entry to each function to check whether the process has used up all its reductions or not. If there are reductions left the function is executed otherwise the process is suspended.

Now, why would you want to measure this? Well, apart from BIFs & NIFs, which are not accurately tracked through this, it gives an impression of how much work the BEAM is doing. And the great thing is, this is independent of the load the system is under as well as the hardware. Hence, it gives you a way to check performance that is less volatile so suitable for CI for instance.

It can slightly differ between elixir & erlang versions, though.

Like memory measurements, this only tracks reductions directly in the function given to benchee, not processes spawned by it or other processes it uses.

Reduction measurement is disabled by default, you can choose to enable it by passing reduction_time: your_seconds option to Benchee.run/2:

Benchee.run(

%{

"something_great" => fn -> cool_stuff end

},

reduction_time: 2

)

Also like memory measurements, reduction measurements will often be constant unless something changes about the execution of the benchmarking function.

Inputs

:inputs is a very useful configuration that allows you to run the same benchmarking jobs with different inputs. We call this combination a "scenario". You specify the inputs as either a map from name (String or atom) to the actual input value or a list of tuples where the first element in each tuple is the name and the second element in the tuple is the value.

Why do this? Functions can have different performance characteristics on differently shaped inputs - be that structure or input size. One of such cases is comparing tail-recursive and body-recursive implementations of map. More information in the repository with the benchmark and the blog post.

As a little sample:

map_fun = fn i -> [i, i * i] end

Benchee.run(

%{

"flat_map" => fn input -> Enum.flat_map(input, map_fun) end,

"map.flatten" => fn input -> input |> Enum.map(map_fun) |> List.flatten() end

},

inputs: %{

"Small" => Enum.to_list(1..1_000),

"Medium" => Enum.to_list(1..10_000),

"Bigger" => Enum.to_list(1..100_000)

}

)

This means each function will be benchmarked with each input that is specified in the inputs. Then you'll get the output divided by input so you can see which function is fastest for which input, like so:

tobi@speedy:~/github/benchee(readme-overhaul)$ mix run samples/multiple_inputs.exs

(... general information ...)

##### With input Bigger #####

Name ips average deviation median 99th %

flat_map 150.81 6.63 ms ±12.65% 6.57 ms 8.74 ms

map.flatten 114.05 8.77 ms ±16.22% 8.42 ms 12.76 ms

Comparison:

flat_map 150.81

map.flatten 114.05 - 1.32x slower +2.14 ms

##### With input Medium #####

Name ips average deviation median 99th %

flat_map 2.28 K 437.80 μs ±10.72% 425.63 μs 725.09 μs

map.flatten 1.78 K 561.18 μs ±5.55% 553.98 μs 675.98 μs

Comparison:

flat_map 2.28 K

map.flatten 1.78 K - 1.28x slower +123.37 μs

##### With input Small #####

Name ips average deviation median 99th %

flat_map 26.31 K 38.01 μs ±15.47% 36.69 μs 67.08 μs

map.flatten 18.65 K 53.61 μs ±11.32% 52.79 μs 70.17 μs

Comparison:

flat_map 26.31 K

map.flatten 18.65 K - 1.41x slower +15.61 μs

Therefore, we highly recommend using this feature and checking different realistically structured and sized inputs for the functions you benchmark!

Formatters

Among all the configuration options, one that you probably want to use are the formatters. They format and print out the results of the benchmarking suite.

The :formatters option is specified a list of:

- modules implementing the

Benchee.Formatterbehaviour - a tuple of a module specified above and options for it

{module, options} - functions that take one argument (the benchmarking suite with all its results) and then do whatever you want them to

So if you are using the HTML plugin and you want to run both the console formatter and the HTML formatter this looks like this (after you installed it of course):

list = Enum.to_list(1..10_000)

map_fun = fn i -> [i, i * i] end

Benchee.run(

%{

"flat_map" => fn -> Enum.flat_map(list, map_fun) end,

"map.flatten" => fn -> list |> Enum.map(map_fun) |> List.flatten end

},

formatters: [

{Benchee.Formatters.HTML, file: "samples_output/my.html"},

Benchee.Formatters.Console

]

)

Console Formatter options

The console formatter supports 2 configuration options:

:comparison- if the comparison of the different benchmarking jobs (x times slower than) is shown. Enabled by default.extended_statistics- display more statistics, akaminimum,maximum,sample_sizeandmode. Disabled by default.

So if you want to see more statistics you simple pass extended_statistics: true to the console formatter:

list = Enum.to_list(1..10_000)

map_fun = fn i -> [i, i * i] end

Benchee.run(

%{

"flat_map" => fn -> Enum.flat_map(list, map_fun) end,

"map.flatten" => fn -> list |> Enum.map(map_fun) |> List.flatten() end

},

time: 10,

formatters: [{Benchee.Formatters.Console, extended_statistics: true}]

)

Which produces:

(... normal output ...)

Extended statistics:

Name minimum maximum sample size mode

flat_map 345.43 μs 1195.89 μs 23.73 K 405.64 μs

map.flatten 522.99 μs 2105.56 μs 12.03 K 767.83 μs, 768.44 μs

(Btw. notice how the modes of both are much closer and for map.flatten much less than the average of 766.99, see samples/run_extended_statistics)

Profiling after a run

Often time when benchmarking, you want to improve performance. However, Benchee only tells you how fast something is, it doesn't tell you what part of your code is slow. This is where profiling comes in.

Benchee offers you the profile_after option to run a profiler of your choice after a benchmarking run to see what's slow. This will run every scenario once.

By default it will run the :eprof profiler, different profilers with different options can be used - see configuration.

list = Enum.to_list(1..10_000)

map_fun = fn i -> [i, i * i] end

Benchee.run(

%{

"flat_map" => fn -> Enum.flat_map(list, map_fun) end,

"map.flatten" => fn -> list |> Enum.map(map_fun) |> List.flatten() end

},

profile_after: true

)

After the normal benchmarking, this results prints profiles like:

Profiling flat_map with eprof...

Warmup...

Profile results of #PID<0.1885.0>

# CALLS % TIME µS/CALL

Total 30004 100.0 5665 0.19

Enum.flat_map/2 1 0.00 0 0.00

anonymous fn/2 in :elixir_compiler_1.__FILE__/1 1 0.00 0 0.00

:erlang.apply/2 1 0.04 2 2.00

:erlang.++/2 10000 18.38 1041 0.10

anonymous fn/1 in :elixir_compiler_1.__FILE__/1 10000 28.12 1593 0.16

Enum.flat_map_list/2 10001 53.47 3029 0.30

Profile done over 6 matching functions

Profiling map.flatten with eprof...

Warmup...

Profile results of #PID<0.1887.0>

# CALLS % TIME µS/CALL

Total 60007 100.0 8649 0.14

Enum.map/2 1 0.00 0 0.00

anonymous fn/2 in :elixir_compiler_1.__FILE__/1 1 0.00 0 0.00

List.flatten/1 1 0.00 0 0.00

:lists.flatten/1 1 0.00 0 0.00

:erlang.apply/2 1 0.02 2 2.00

anonymous fn/1 in :elixir_compiler_1.__FILE__/1 10000 16.35 1414 0.14

Enum."-map/2-lists^map/1-0-"/2 10001 26.38 2282 0.23

:lists.do_flatten/2 40001 57.24 4951 0.12

Note about after_each hooks: after_each hooks currently don't work when profiling a function, as they are not passed the return value of the function after the profiling run. It's already fixed on the elixir side and is waiting for release, likely in 1.14. It should then just work.

Saving, loading and comparing previous runs

Benchee can store the results of previous runs in a file and then load them again to compare them. For example this is useful to compare what was recorded on the main branch against a branch with performance improvements. You may also use this to benchmark across different exlixir/erlang versions.

Saving is done through the :save configuration option. You can specify a :path where results are saved, or you can use the default option of"benchmark.benchee" if you don't pass a :path. You can also pass a :tag option which annotates these results (for instance with a branch name or elixir version number). The default option for the :tag is a timestamp of when the benchmark was run.

Loading is done through the :load option specifying a path to the file to load (for instance "benchmark.benchee"). You can also specify multiple files to load through a list of paths (["my.benchee", "main_save.benchee"]) - each one of those can also be a glob expression to match even more files glob ("save_number*.benchee").

In the more verbose API loading is triggered via Benchee.load/1.

If all you want to do is to use :load without running any benchmarks then you can use Benchee.report/1 which will take a normal configuration with a :load key and just format the loaded saved results with the given formatters.

Benchee.run(

%{

"something_great" => fn -> cool_stuff end

},

save: [path: "save.benchee", tag: "first-try"]

)

Benchee.report(load: "save.benchee")

Hooks (Setup, Teardown etc.)

Most of the time, it's best to keep your benchmarks as simple as possible: plain old immutable functions work best. But sometimes you need other things to happen. When you want to add before or after hooks to your benchmarks, we've got you covered! Before you dig into this section though remember one thing: you usually don't need hooks!

Benchee has three types of hooks:

Of course, hooks are not included in the measurements. So they are there especially if you want to do something and want it to not be included in the measurements. Sadly there is the notable exception of too_fast_functions (the ones that execute faster than we can measure in native resolution). As we need to measure their repeated invocations to get halfway good measurements before_each and after_each hooks are included there. However, to the best of our knowledge this should only ever happen on Windows (because of the bad run time measurement accuracy).

Suite hooks

It is very easy in Benchee to do setup and teardown for the whole benchmarking suite (think: "before all" and "after all"). As Benchee is just plain old functions, just do your setup and teardown before/after you call Benchee:

your_setup()

Benchee.run(%{"Awesome stuff" => fn -> magic end})

your_teardown()

When might this be useful?

- Seeding the database with data to be used by all benchmarking functions

- Starting/shutting down a server, process, other dependencies

Scenario hooks

For the following discussions, it's important to know what benchee considers a "benchmarking scenario".

What is a scenario?

A scenario is the combination of one benchmarking function and one input. So, given this benchmark:

Benchee.run(

%{

"foo" => fn input -> ... end,

"bar" => fn input -> ... end

},

inputs: %{

"input 1" => 1,

"input 2" => 2

}

)

there are 4 scenarios:

- foo with input 1

- foo with input 2

- bar with input 1

- bar with input 2

A scenario includes warmup and actual run time (+ other measurements like memory).

before_scenario

Is executed before every scenario that it applies to (see hook configuration). before_scenario hooks take the input of the scenario as an argument.

Since the return value of a before_scenario becomes the input for next steps (see hook arguments and return values), there usually are 3 kinds of before scenarios:

- you just want to invoke a side effect: in that case return the given input unchanged

- you want to alter the given input: in that case alter the given input

- you want to keep the given input but add some other data: in that case return a tuple like

{original_input, new_fancy_data}

For before scenario hooks, the global hook is invoked first, then the local (see when does a hook happen?).

Usage:

Benchee.run(

%{

"foo" =>

{

fn {input, resource} -> foo(input, resource) end,

before_scenario: fn {input, resource} ->

resource = alter_resource(resource)

{input, resource}

end

},

"bar" =>

fn {input, resource} -> bar(input, resource) end

},

inputs: %{"input 1" => 1},

before_scenario: fn input ->

resource = start_expensive_resource()

{input, resource}

end

)

When might this be useful?

- Starting a process to be used in your scenario

- Recording the PID of

self()for use in your benchmark (each scenario is executed in its own process, so scenario PIDs aren't available in functions running before the suite) - Clearing the cache before a scenario

after_scenario

Is executed after a scenario has completed. After scenario hooks receive the return value of the last before_scenario that ran as an argument. The return value is discarded (see hook arguments and return values).

For after scenario hooks, the local hook is invoked first, then the global (see when does a hook happen?).

Usage:

Benchee.run(

%{

"bar" => fn -> bar() end

},

after_scenario: fn _input -> bust_my_cache() end

)

When might this be useful?

- Busting caches after a scenario completed

- Deleting all the records in the database that the scenario just created

- Terminating whatever was setup by

before_scenario

Benchmarking function hooks

You can also schedule hooks to run before and after each invocation of a benchmarking function.

before_each

Is executed before each invocation of the benchmarking function (before every measurement). Before each hooks receive the return value of their before_scenario hook as their argument. The return value of a before each hook becomes the input to the benchmarking function (see hook arguments and return values).

For before each hooks, the global hook is invoked first, then the local (see when does a hook happen?).

Usage:

Benchee.run(

%{

"bar" => fn record -> bar(record) end

},

inputs: %{ "record id" => 1},

before_each: fn input -> get_from_db(input) end

)

When might this be useful?

- Retrieving a record from the database and passing it on to the benchmarking function to do something(tm) without the retrieval from the database adding to the benchmark measurement

- Busting caches so that all measurements are taken in an uncached state

- Picking a random value from a collection and passing it to the benchmarking function for measuring performance with a wider spread of values

- you could also use this to benchmark with random data like

StreamData, devon shows how it's done here

after_each

Is executed directly after the invocation of the benchmarking function. After each hooks receive the return value of the benchmarking function as their argument. The return value is discarded (see hook arguments and return values).

For after each hooks, the local hook is invoked first, then the global (see when does a hook happen?).

Usage:

Benchee.run(

%{

"bar" => fn input -> bar(input) end

},

inputs: %{ "input 1" => 1},

after_each: fn result -> assert result == 42 end

)

When might this be useful?

- Running assertions that whatever your benchmarking function returns is truly what it should be (i.e. all "contestants" work as expected)

- Busting caches/terminating processes setup in

before_eachor elsewhere - Deleting files created by the benchmarking function

Hook arguments and return values

Before hooks form a chain, where the return value of the previous hook becomes the argument for the next one. The first defined before hook receives the scenario input as an argument, and returns a value that becomes the argument of the next in the chain. The benchmarking function receives the value of the last before hook as its argument (or the scenario input if there are no before hooks).

After hooks do not form a chain, and their return values are discarded. An after_each hook receives the return value of the benchmarking function as its argument. An after_scenario function receives the return value of the last before_scenario that ran (or the scenario's input if there is no before_scenario hook).

If you haven't defined any inputs, the hook chain is started with the special input argument returned by Benchee.Benchmark.no_input().

Hook configuration: global versus local

Hooks can be defined either globally as part of the configuration or locally for a specific benchmarking function. Global hooks will be executed for every scenario in the suite. Local hooks will only be executed for scenarios involving that benchmarking function.

Global hooks

Global hooks are specified as part of the general benchee configuration:

Benchee.run(

%{

"foo" => fn input -> ... end,

"bar" => fn input -> ... end

},

inputs: %{

"input 1" => 1,

"input 2" => 2,

},

before_scenario: fn input -> ... end

)

Here the before_scenario function will be executed for all 4 scenarios present in this benchmarking suite.

Local hooks

Local hooks are defined alongside the benchmarking function. To define a local hook, pass a tuple in the initial map, instead of just a single function. The benchmarking function comes first, followed by a keyword list specifying the hooks to run:

Benchee.run(

%{

"foo" => {fn input -> ... end, before_scenario: fn input -> ... end},

"bar" => fn input -> ... end

},

inputs: %{

"input 1" => 1,

"input 2" => 2

}

)

Here before_scenario is only run for the 2 scenarios associated with "foo", i.e. foo with input 1 and foo with input 2. It is not run for any "bar" benchmarks.

When does a hook happen? (Complete Example)

Yes the whole hooks system is quite a lot to take in. Here is an overview showing the order of hook execution, along with the argument each hook receives (see hook arguments and return values). The guiding principle whether local or global is run first is that local always executes closer to the benchmarking function.

Given the following code:

suite_set_up()

Benchee.run(

%{

"foo" =>

{

fn input -> foo(input) end,

before_scenario: fn input ->

local_before_scenario(input)

input + 1

end,

before_each: fn input ->

local_before_each(input)

input + 1

end,

after_each: fn value ->

local_after_each(value)

end,

after_scenario: fn input ->

local_after_scenario(input)

end

},

"bar" =>

fn input -> bar(input) end

},

inputs: %{"input 1" => 1},

before_scenario: fn input ->

global_before_scenario(input)

input + 1

end,

before_each: fn input ->

global_before_each(input)

input + 1

end,

after_each: fn value ->

global_after_each(value)

end,

after_scenario: fn input ->

global_after_scenario(input)

end

)

suite_tear_down()

Keeping in mind that the order of foo and bar could be different, here is how the hooks are called:

suite_set_up

# starting with the foo scenario

global_before_scenario(1)

local_before_scenario(2) # as before_scenario incremented it

global_before_each(3)

local_before_each(4)

foo(5) # let's say foo(5) returns 6

local_after_each(6)

global_after_each(6)

global_before_each(3)

local_before_each(4)

foo(5) # let's say foo(5) returns 6

local_after_each(6)

global_after_each(6)

# ... this block is repeated as many times as benchee has time

local_after_scenario(3)

global_after_scenario(3)

# now it's time for the bar scenario, it has no hooks specified for itself

# so only the global hooks are run

global_before_scenario(1)

global_before_each(2)

bar(3) # let's say foo(3) returns 4

global_after_each(4)

global_before_each(2)

bar(3) # let's say foo(3) returns 4

global_after_each(4)

# ... this block is repeated as many times as benchee has time

global_after_scenario(2)

suite_tear_down

More verbose usage

It is important to note that the benchmarking code shown in the beginning is the convenience interface. The same benchmark in its more verbose form looks like this:

list = Enum.to_list(1..10_000)

map_fun = fn i -> [i, i * i] end

[time: 3]

|> Benchee.init()

|> Benchee.system()

|> Benchee.benchmark("flat_map", fn -> Enum.flat_map(list, map_fun) end)

|> Benchee.benchmark(

"map.flatten",

fn -> list |> Enum.map(map_fun) |> List.flatten() end

)

|> Benchee.collect()

|> Benchee.statistics()

|> Benchee.relative_statistics()

|> Benchee.Formatter.output(Benchee.Formatters.Console)

# Instead of the last call you could also just use Benchee.Formatter.output()

# to just output all configured formatters

This is a take on the functional transformation of data applied to benchmarks:

- Configure the benchmarking suite to be run

- Gather System data

- Define the functions to be benchmarked

- Run benchmarks with the given configuration gathering raw run times per function

- Calculate statistics based on the raw run times

- Calculate statistics between the scenarios (faster/slower...)

- Format the statistics in a suitable way and print them out

This is also part of the official API and allows for more fine grained control. (It's also what Benchee does internally when you use Benchee.run/2).

Do you just want to have all the raw run times? Just work with the result of Benchee.collect/1! Just want to have the calculated statistics and use your own formatting? Grab the result of Benchee.statistics/1! Or, maybe you want to write to a file or send an HTTP post to some online service? Just grab the complete suite after statistics were generated.

It also allows you to alter behaviour, normally Benchee.load/1 is called right before the formatters so that neither the benchmarks are run again or statistics are computed again. However, you might want to run the benchmarks again or recompute the statistics. Then you can call Benchee.load/1 right at the start.

This way Benchee should be flexible enough to suit your needs and be extended at will. Have a look at the available plugins.

Usage from Erlang

Before you dig deep into this, it is inherently easier to setup a small elixir project, add a dependency to your erlang project and then run the benchmarks from elixir. The reason is easy - mix knows about rebar3 and knows how to work with it. The reverse isn't true so the road ahead is somewhat bumpy.

There is an example project to check out.

You can use the rebar3_elixir_compile plugin. In your rebar.config you can do the following which should get you started:

deps, [

{benchee, {elixir, "benchee", "0.9.0"}}

]}.

{plugins, [

{ rebar3_elixir_compile, ".*", {git, "https://github.com/barrel-db/rebar3_elixir_compile.git", {branch, "main"}}}

]}.

{provider_hooks, [

{pre, [{compile, {ex, compile}}]},

{pre, [{release, {ex, compile}}]}

]}.

{elixir_opts,

[

{env, dev}

]

}.

Then benchee already provides a :benchee interface for erlang compatibility which you can use. Sadly couldn't get it to work in an escript yet.

You can then invoke it like this (for instance):

tobi@comfy ~/github/benchee_erlang_try $ rebar3 shell

===> dependencies etc.

Erlang/OTP 18 [erts-7.3] [source] [64-bit] [smp:4:4] [async-threads:0] [hipe] [kernel-poll:false]

Eshell V7.3 (abort with ^G)

1> benchee:run(#{myFunc => fun() -> lists:sort([8, 2, 3, 4, 2, 1, 3, 4, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 20, 1000, -4, -5]) end}, [{warmup, 0}, {time, 2}]).

Operating System: Linux

CPU Information: Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-7200U CPU @ 2.50GHz

Number of Available Cores: 4

Available memory: 8.05 GB

Elixir 1.3.4

Erlang 18.3

Benchmark suite executing with the following configuration:

warmup: 0.0 μs

time: 2 s

parallel: 1

inputs: none specified

Estimated total run time: 2 s

Benchmarking myFunc...

Name ips average deviation median

myFunc 289.71 K 3.45 μs ±250.31% 3 μs

This doesn't seem to be too reliable right now, so suggestions and input are very welcome :)

Known Issues

There is a known issue affecting elixir versions from 1.14.0 to 1.16.0-rc.0: Optimizations (SSA and bool passes, see the original change) had been disabled affecting the performance of functions defined directly in the top level (i.e. outside of any module). The issue was fixed by re-enabling the optimization in 1.16.0-rc.1. The issue is best show-cased by the following benchmark where we'd expect ~equal results:

list = Enum.to_list(1..10_000)

defmodule Compiled do

def comprehension(list) do

for x <- list, rem(x, 2) == 1, do: x + 1

end

end

Benchee.run(%{

"module (optimized)" => fn -> Compiled.comprehension(list) end,

"top_level (non-optimized)" => fn -> for x <- list, rem(x, 2) == 1, do: x + 1 end

})

Which yields ~these results on an affected elixir version:

Comparison:

module (optimized) 18.24 K

top_level (non-optimized) 11.91 K - 1.53x slower +29.14 μs

So, how do you fix it/make sure a benchmark you ran is not affected? All of these work:

- benchmark on an unaffected/fixed version of elixir (<= 1.13.4 or >= 1.16.0-rc.1)

- put the code you want to benchmark into a module (just like it is done in

Compiledin the example above) - you can also invoke benchee from within a module, such as:

defmodule Compiled do

def comprehension(list) do

for x <- list, rem(x, 2) == 1, do: x + 1

end

end

defmodule MyBenchmark do

def run do

list = Enum.to_list(1..10_000)

Benchee.run(%{

"module (optimized)" => fn -> Compiled.comprehension(list) end,

"top_level (non-optimized)" => fn -> for x <- list, rem(x, 2) == 1, do: x + 1 end

})

end

end

MyBenchmark.run()

Also note that even if all your examples are top level functions you should still follow these tips (on affected elixir versions), as the missing optimization might affect them differently. Further note, that even though your examples use top level functions they may not be affected, as the specific disabled optimization may not impact them. Better safe than sorry though :)

Plugins

Benchee only has small runtime dependencies that were initially extracted from it. Further functionality is provided through plugins that then pull in dependencies, such as HTML generation and CSV export. They help provide excellent visualization or interoperability.

- benchee_html - generate HTML including a data table and many different graphs with the possibility to export individual graphs as PNG :)

- benchee_csv - generate CSV from your benchee benchmark results so you can import them into your favorite spreadsheet tool and make fancy graphs

- benchee_json - export suite results as JSON to feed anywhere or feed it to your JavaScript and make magic happen :)

- benchee_markdown - write markdown files containing your benchmarking results

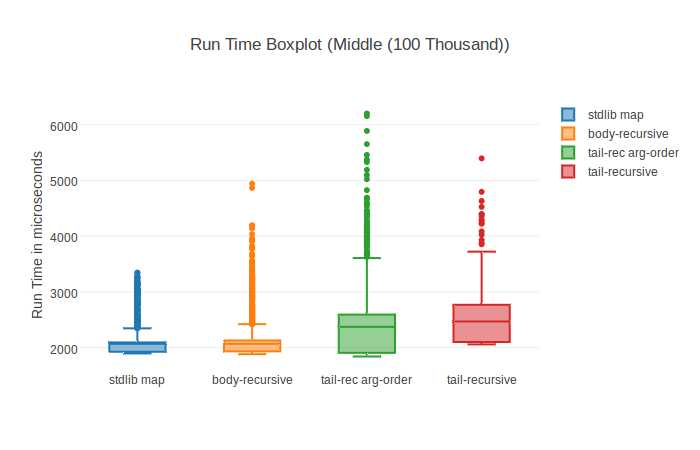

With the HTML plugin for instance you can get fancy graphs like this boxplot:

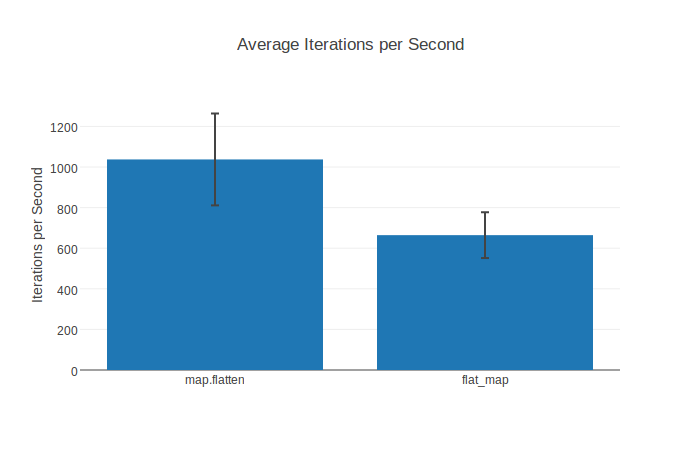

Of course there also are normal bar charts including standard deviation:

Contributing

Contributions to Benchee are very welcome! Bug reports, documentation, spelling corrections, whole features, feature ideas, bugfixes, new plugins, fancy graphics... all of those (and probably more) are much appreciated contributions!

Keep in mind that the plugins live in their own repositories with their own issue tracker and they also like to get contributions :)

Please respect the Code of Conduct.

In addition to contributing code, you can help to triage issues. This can include reproducing bug reports, or asking for vital information such as version numbers or reproduction instructions. If you would like to start triaging issues, one easy way to get started is to subscribe to pragtob/benchee on CodeTriage.

You can also look directly at the open issues. There are help wanted and good first issue labels - those are meant as guidance, of course other issues can be tackled :)

A couple of (hopefully) helpful points:

- Feel free to ask for help and guidance on an issue/PR ("How can I implement this?", "How could I test this?", ...)

- Feel free to open early/not yet complete pull requests to get some early feedback

- When in doubt if something is a good idea open an issue first to discuss it

- In case I don't respond feel free to bump the issue/PR or ping me in other places

If you're on the elixir-lang slack also feel free to drop by in #benchee and say hi!

Development

Note that if the change includes adding new statistics you might need to introduce them to our statistics library Statistex first!

mix deps.getto install dependenciesmix testto run testsmix dialyzerto run dialyzer for type checking, might take a while on the first invocation (try building plts first withmix dialyzer --plt)mix credoto find code style problems- or run

mix guardto run all of them continuously on file change

Copyright and License

Copyright (c) 2016 Tobias Pfeiffer

This work is free. You can redistribute it and/or modify it under the terms of the MIT License. See the LICENSE.md file for more details.